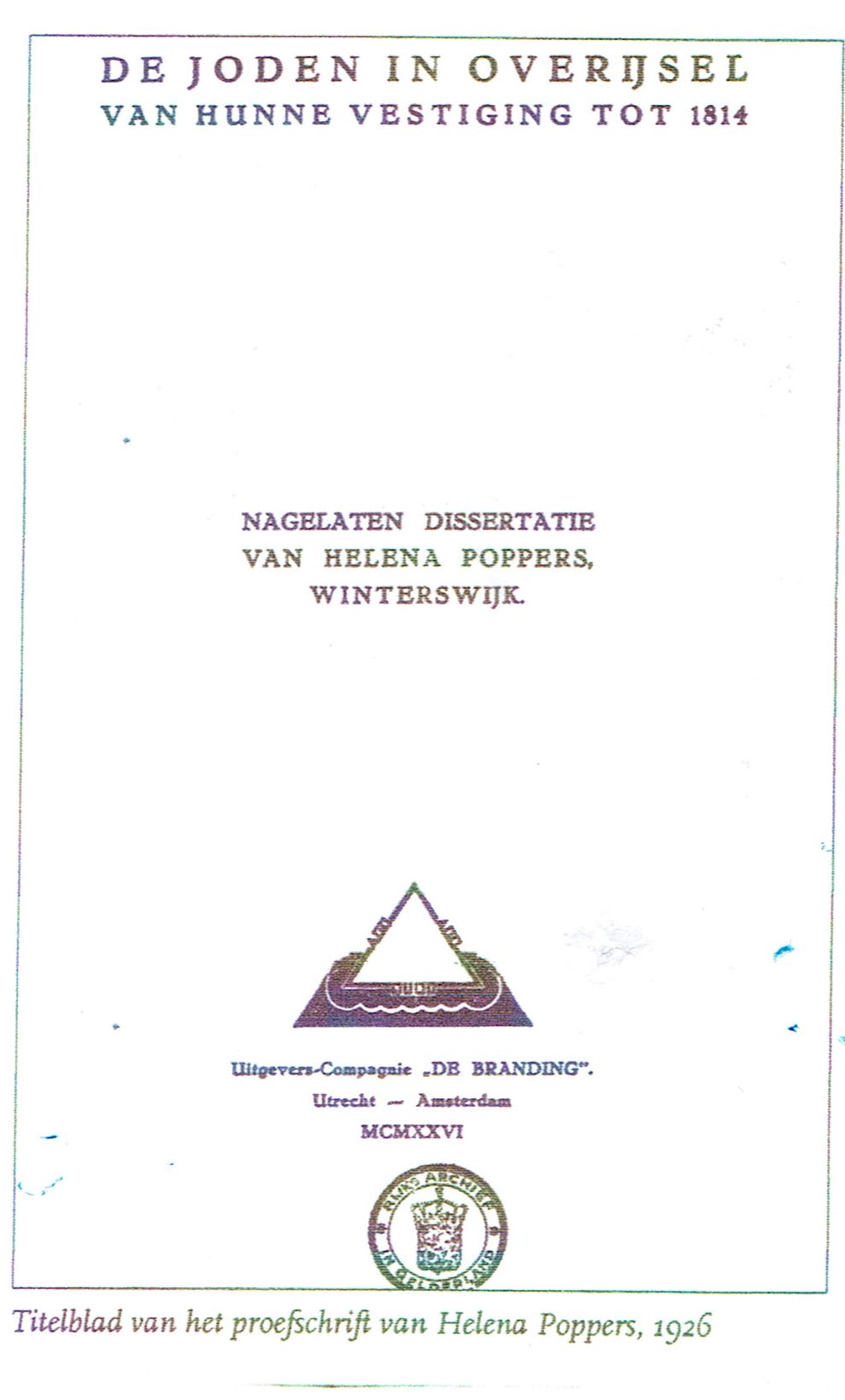

The Jews in Overijssel from their first settlement to 1814

Source: Helena Poppers’ posthumous thesis

Register van joodse namen (samengesteld uit de thesis door Marianne Slager).

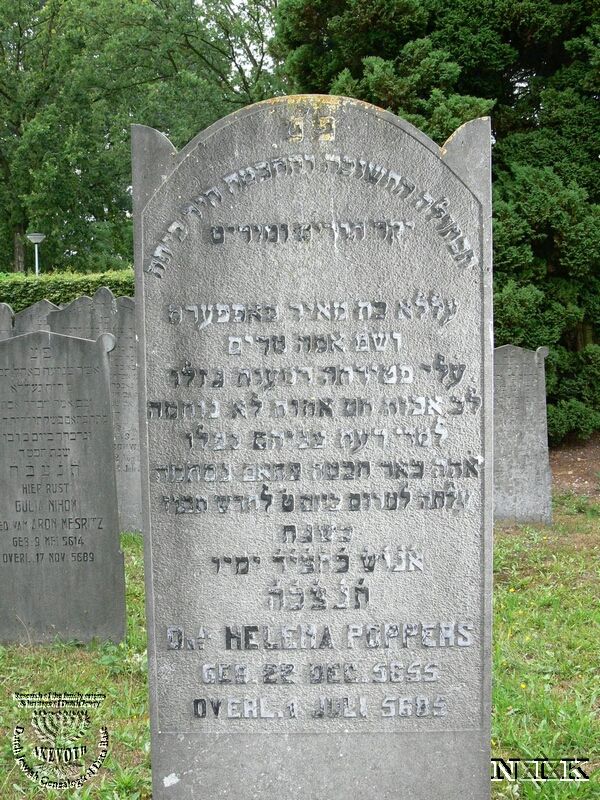

Helena Poppers was born in Winterswijk in 1895. She died after a short illness in 1925 and was unable to complete her thesis.

Helena Poppers died on 1 July in 1925, shortly after the completion of her important thesis, which received the title De Joden in Overijssel van hunne vestiging tot 1814 (The Jews in Overijssel from their first settlement to 1814).

Helena was born on 22 December 1895 and died when she was only 30. After primary and secondary school she took the university entrance exam in August 1915. She studied Dutch language and literature at the University of Groningen under professors Gosses, Kluyver and Sijmons.

She continued her studies at the University of Leiden and obtained her Master’s on 30 September 1921. She decided to write a thesis in August 1923, “by choice on an episode in the History of the Jews in the Netherlands”.

In the course of 1925 she completed seven chapters. She used some of her notes for an article in the Jewish weekly De Vrijdagavond in 1925. Before she could make the corrections her supervisor professor Gosses had suggested, and add a conclusion, a short illness put an end to her life.

Her parents commissioned Sigmund Seeligman in Amsterdam to prepare Helena’s text and notes for publication. The thesis appeared posthumously in 1926. The document still makes a valuable contribution to the history of the mediene [Jewish communities outside Amsterdam].

Introduction

There are no traces of Jews in Overijssel during Charlemagne’s reign in the late 8th and early 9th centuries. The earliest information we have about Oversticht, as Overijssel was formerly known, dates from the first half of the 14th century. Although Jews had played a large part in the commercial world of the German empire before the 12th century, they were still refused entry to Overijssel in the 14th century. The only occupation open to them was money lending, an occupation forbidden to Christians. Jewish possessions were at that time often seized by noblemen. The outbreak of the plague in the summer of 1349 brought death to Overijssel inhabitants and to Jewish moneylenders. The Jews were blamed for having poisoned the wells and many of them were murdered as a result.

One Jewish person is known to have lived for some time in Deventer, but there are no reports of other Jews in Overijssel during the 14th century. Those who did appear occasionally were subject to strict prohibitions.

Jews recorded in the 16th century included a moneylender and two doctors (Hasselt). During the Eighty Years’ War there were no Jews in Overijssel, as they were not welcome during that entire time.

The Jews of Overijssel in the 17th century

Portuguese and Spanish Jews did not play an important role in Overijssel. German and Polish Jews dominated, but were only admitted in small numbers at first.

As the aversion to Jews gradually disappeared, they were allowed to settle, to start with mostly in Zwolle (the province’s capital), but later also in Deventer, Kampen and some smaller places. Most of the local objections against Jews were for religious and economic reasons, mainly because the inhabitants were unfamiliar with them and their religion, and initially objected to their street trading. As time went by the locals became more tolerant.

In the seventeenth century Jews settled in other smaller cities as well. Thus a pawnshop in Enschede was run by a Jew, in 1679 a Jew was admitted to the small town of Goor in the eastern part of the province, and towards the end of the 17th century a Jewish butcher was allowed to settle in Ootmarsum. The number of Jews in the province during that period remained extremely small, even though their living conditions, as far as religion and municipal taxes were concerned, were reasonable.

The Jews outside Overijssel’s capital in the 18th century

In the course of the 18th century Jews were admitted to several places in Overijssel, where they could freely practice their religion and, considering the time they lived in, were treated decently in other respects as well.

Jews settled in Almelo, Blokzijl, Borne, Denekamp, Delden, Diepenheim, Enschede, Enter, Goor, Haaksbergen, Hardenberg, Hasselt, Hengelo, Kampen, Losser, Markelo, Oldenzaal, Ommen, Ootmarsum, Raalte, Rijssen and Wijhe. Kampen, one of Overijssel’s largest cities, occupied a special place among them. Towards the middle of the 18th century several Jewish families had settled there and their numbers increased. Entry conditions and admission decisions were in the hands of the city council. Jews could live in Kampen without fear of being expelled or of having to pay extra taxes. Towards the end of the 18th century a number of Jews gained citizenship, either as grootburgers (with more rights) or kleinburgers (with fewer rights), and were thus able to gain entry to the pedlars’ guild.

In the smaller cities the decision to admit Jews was the responsibility of the town council or the district sheriff. Final decision often rested with the nobles and the cities. In Hasselt and Steenwijk the authorities were lenient because of speculative trade. Whether this encouraged Jews to settle there, is not clear. In most of the smaller cities Jews were allowed to live peacefully and ply their trade. In Ootmarsum and Diepenheim they could even own houses, but if they settled there without permission, they ran the risk of being banished.

The number of Jews in these parts amounted to only a small percentage of the population as a whole.

In the 17th and 18th century a few cities in Overijssel, such as Deventer and Steenwijk, did not admit Jews.

At that time Jews in the Netherlands did not enjoy the same legal status as the rest of the population. While all legal matters were settled by a secular judge, Jews had to use an appropriately worded eedsformulier (oath form). They were however generally treated fairly in lawsuits. When Jews were getting married, their banns would be read out in a Protestant church.

Language and personal relationships

Jews in the Netherlands spoke a mixture of German, Polish and Hebrew, and used Hebrew in writing. As far as personal relationships were concerned, they largely had to rely on each other, and often lived in with parents, brothers or sisters.

Kampen

Although Kampen had the largest Jewish community in Overijssel, it is not known when it came into existence. In 1760 the Jewish community informed the city council of discord among them and asked to be given a set of rules. This did not put an end to the arguments however. The Jewish community therefore decided to follow the example of the communities in Amsterdam and Zwolle and establish a kerkeraad (church council). A kerkeraad was duly formed, consisting of five members including two Parnassim.

For about ten years peace reigned, until new problems surfaced. After these had been solved, unrest broke out again in 1794.

The city council was regularly involved in the affairs of the Jewish community, also economic matters.

The synagogue

Little is known about the synagogue in Kampen, apart from the fact that it was located on the Koornmarkt in 1767, and that there was a caretaker, and a school teacher who probably also functioned as a cantor.

The cemetery

The cemetery was desecrated in 1779. Whether it was an antisemitic incident or an act of vandalism is not clear. It may have been the latter, as damage was also done to areas outside the cemetery.

The smaller communities

The smaller communities were not governed by sets of rules. Its members did not pay tax for renting synagogue seats for example. Income was generated through collections. Services were generally held in someone’s home, and there would be a cemetery. In Hasselt the Jews were given a plot of land, and in 1740 a Jew was buried in Losser.

Economy

How the Jews fared economically, is difficult to ascertain, as we do not have enough facts at our disposal. They earned their livings as butchers, cattle dealers, and selling hides and an assortment of goods.

In the eastern part of Overijssel they mostly earned their living selling goods. They bought surplus goods from farmers - such as hay, oats, cattle, hides and agricultural products - and provided the rural community with cattle, linseed, clothing and lottery tickets (for large and small amounts of money).

Jewish shops in that area sold a great variety of goods such as groceries, spices, textile and meat. The poorest Jews traded in hair, junk and rags.

In Overijssel as well as in Germany there were Jewish army suppliers.

Obstructing Jewish trade

In Kampen Jews competed against each other for trade. There was no resistance from Christians against Jewish trade in the 18th century. In the other parts of Overijssel Jews were generally able to trade freely in the small towns and villages, mainly because there were no merchant guilds.

Relationships with farmers were on the whole good as far as trade was concerned. The farmers sold cattle and cereals to the Jews.

Antisemitism and antisocial elements

Although Jews were generally met with tolerance, there was evidence of antisemitism in the courts of law. Insults concerned the Jewish religion and Jewish decent.

Jews were often of foreign origin and needed to be considered as criminals. In 1722 there happened to be a Jewish criminal gang whose members came from different states of the German empire and other countries in Europe. Because the criminals usually operated in the countryside, Jewish vagrants and merchants were restricted in their movements. The punishment for criminals was usually flogging, branding and banishment from the province.

Jewish vagrants and beggars were not allowed to stay in the small towns and villages, and it was forbidden to give them shelter.

Zwolle before 1795

The relationship between Jews and Christians was generally good, and that was also the case in Zwolle. The Magistrate of the city rarely made use of restrictions against Jews. There was no ghetto, and they could exercise their religion in peace. The regents of the city showed great tolerance towards the Jews with regard to commercial interests. Yet there were restrictions, especially when it concerned entry into guilds and the holding of office.

In the first decade of the 18th century few Jews settled in Zwolle, but around 1720 that changed. With the growth of financial speculation Jewish shareholders, most of them Portuguese Jews, were also attracted.

At some point the increasing number of Jews began to cause concern, and between 1753 and 1788 few Jews were admitted. Those who remained were subject to all kinds of restrictions and difficulties. Yet the city council and the Parnassim worked together to keep out undesirable elements, and the Jews who had obtained citizenship had certain privileges.

Means of existence

The Jewish community in Zwolle counted among its members traders in hides and textiles, a cereal wholesaler, a dyer of materials and clothes, and butchers and cattle dealers. Most guilds did not admit Jews, but those with citizenship were allowed entry to the pedlars’ guild, and a little later also to the Pelzer guild and the guild for white leather preparation. There was a Jewish doctor who treated both Jews and Christians, and in 1790 there was also a Jewish midwife. Jews from Germany, Poland, France or Bohemia enjoyed privileges which they had not known in their own country.

The cooperation of German Jews in Zwolle was important for the annual fair in the city which was actually held biannually. The larger and better assortment of clocks, books, mirrors, hats and silverware offered its inhabitants more choice. The stall holders also contributed greatly to the flourishing of the Leipziger Messe (the famous fair in Leipzig).

[See also:-The Leipziger Messe as a source in genealogy :- The prayer for the government which had been in use until then, had to be replaced by another one in which God was implored to ensure the wellbeing of Israel, to make this people worthy of Napoleon.

The execution of these decisions was the responsibility of the Jewish communities. All marriages had to take place in synagogue, and services could also only be held inside a synagogue. These were some of the changes which were brought about for Jewish communities during the French Period. Details about some Jewish communities Zwolle During the French Period the rules from 1747 formed the basis for the Jewish community in Zwolle until 1769. The financial situation of the community was satisfactory. A shortfall of 817 guilders was cleared by voluntary contributions, which were raised by the reading of the Books of Moses in synagogue. However the relocation of the Jewish cemetery created financial difficulties for the community. Relations with the city council did not regain their 18th century character, mainly because of the separation between church and state. Once the Upper Consistory was established, relations between the city council and the Jewish community were severed completely. According to the constitution of 1798 all ecclesiastical goods would become nationalised. The city council therefore informed the Jewish community that they would have to pay an annual sum of 35 guilders for their church building and grounds and 14 guilders for their cemetery. They protested but to no avail, and until 1814 the amounts were apparently duly paid. Until 1813 relief for the poor remained as it had been in the 18th century. Hartog Jozua Hertzveld was the first Chief Rabbi from Zwolle. He was Chief Rabbi for the entire province of Overijssel and part of the province of Gelderland, and was evidently very popular. His salary in Zwolle was 600 guilders and included free housing. Deventer In 1798 the city of Deventer bought a building to serve as synagogue. It had a room where meetings could be held, and the garden could be used as a cemetery for members of the community. The council in Deventer consisted of a Parnas, two treasurers and two ordinary members. As some were related, this inevitably caused problems. In 1809 the community had a cantor and caretaker in its employ. Kampen In 1804 the poor financial situation in Kampen caused problems. The city council became involved, which did not improve the situation to begin with. The problems were solved in the end however and all remained quiet until another conflict arose a few years later, in connection with the filling of posts. Although the community had sent the Upper Consistory a new set of rules its council had drafted, the 1760 rules remained in place until 1774. Blokzijl In 1791 a home synagogue was set up for the Jews of Blokzijl where they could hold their services. As they did not pay a contribution, the synagogue was considered to belong to the proprietor. Consequently not everyone was admitted. The little income that was generated was used for upkeep and the poor. There was a cemetery which could be used on request. For years the community was satisfied with this procedure. In 1807 the community of Blokzijl and Vollenhoven consisted of 31 members. That same year problems arose, and a separate synagogue was established. When King Louis Napoleon paid them a visit, the tension between the two communities was unbearable. When a few representatives of the newest community lodged a complaint with the King, he instructed the Upper Consistory to mediate. In May 1809 the dispute was settled, but soon there were new disagreements, until peace was restored in 1811. Relations were still difficult in 1813 however. Enschede While Blokzijl was the most turbulent Jewish community in Overijssel during this period, Enschede was probably the poorest. In 1809 there were about 40 Jews in Enschede (eight families). As there were fewer than ten adult men, it was not possible to hold services there. Gradually their number increased, and in 1813 services were held in a small rented room. There was however no money to engage a cantor-teacher. The Jews in Enschede were poor and were supported by general relief for the poor in 1810. They could not even pay their rent. When King William proclaimed himself King of the Netherlands in 1815, the emancipation of the Jews in civil life had not yet come about. The Jews had not adapted sufficiently well to the culture and language of the Christian environment, and their lowly position in Overijssel and elsewhere did not help matters. Moreover the deep-seated aversion of the province’s inhabitants did not make social integration any easier for the Jews. However thanks to King Louis Napoleon guidelines existed which would further the assimilation process. -------------------------------------------------------- Extracted from source: Yael (Lotje) Ben Lev-de Jong

Translated from Dutch: Sara Kirby-Nieweg

Review: Ben Noach

End editing: Sara Kirby-Nieweg & Anthony (Tony) Kirby & Ben Noach

|

| Front page of the thesis of Helena Poppers, 1926 |

|

| Helena Poppers |

|

| Tombstone of Helena Poppers in Winterswijk |