The unbridled energy of Dr. Samuel Sarphati

a short sketch of his life and work

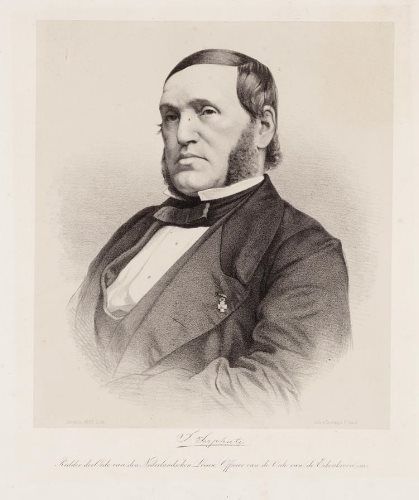

The Sarphati Park, the Sarphati Street, the Sarphati Monument, the Amstel Hotel: many things in Amsterdam remind one of the (medical) Dr. Samuel Sarphati (1813-1866). He is perhaps the most famous “Amsterdammer” of the 19th century. He is thus honored thanks to all he has achieved for this city with his characteristic and unbridled energy.

It is less known that Samuel Sarphati, an orthodox Jew, as a governor of the Portuguese-Jewish Community has also energetically tackled the important matters inside the Jewish community of the 19th century. The following biographical sketch based on recent research draws attention to new facts and findings about his life.

1813

In the year Sarphati was born Holland was bankrupt and plundered. In October Emperor Napoleon suffered an overwhelming defeat near Leipzig and on the 14th of November the French left town. The Portuguese Jews spoke of an inopinada e milagrosa revolucao, an unexpected and miraculous revolution. On November 30th the Prince of Orange arrived from his exile in England on the beach at Scheveningen. On December 2nd he was declared sovereign monarch in Amsterdam and in 1814 he was crowned King William I.

The situation after the French domination was grave. Amsterdam was a city of faded glory. The canals were full of stinking refuse. Many houses had fallen into disrepair or were decayed. The economic progress elsewhere in Europe had passed by the city and the country. The poverty was unimaginably great and hygiene bad. Epidemics (cholera and scarlet fever) broke out and beggars (men, women and children) populated the streets. Samuel Sarphati, who grew up in Jodenbree Street and later on Nieuwe Herengracht, has seen the greatest miseries around him during his youth. One third of the Portuguese and seventy percent of the Ashkenazi Jews lived in those years off charity in the impoverished Jewish Quarter.

Poor-doctor

The parents of Sarphati, Emanuel Sarphati, commissioner of tobacco by profession and Reyna Musafia did not belong, as to their level of welfare, to the higher echelons of the city, but neither were they poor. They were part of the Portuguese-Jewish community, which had settled in Amsterdam from around 1600. The Hebrew word Sarphati (with the accent on the last syllable) means Frenchman; it seems likely that the name refers to the wanderings of their forefathers through that country.

Emanuel and Reyna Sarphati were able to give a good education (the Latin school), to their son Samuel ,with the help of more well-to-do friends and family, and to let him study medicine. Apart from this he also studied pharmacology. During his studies he won several prizes. In June 1839 he was conferred his doctor's degree in Leiden. His thesis (in Latin) about two medical problems is kept in the library of the Amsterdam City Archives: it is dedicated to his 'parentibus optimis carissimis', his greatly beloved parents.

On Friday 10th and Shabbath 11th January 1840 it was announced in the Snoge (the Portuguese synagogue) that the post of physician for the Sephardic community was vacant. Sarphati was the only one who applied and was accepted at a salary of 250 guilders per year. He took up his duties on February 1st, 1840. He had to look after the poor and sick who were admitted in Meshiev Nefesh. The hospital Meshiev Nefesh (Comfort of the Soul) was established in 1835 after an outburst of cholera the year before.

The first confrontation between the very conservative parnassim of that time and the young energetic physician came in 1842 when the rules of the hospital and the instructions to the physicians had to be changed. Sarphati had a suggestion in this connection and wanted to come in person to explain this to the parnassim. After insisting for a long time, he received permission but the visit ended up in an unpleasant exchange of words. The parnassim found the arguments to be of "too little weight" and seemingly they held the same opinion of the personality of the young doctor himself.

Wedding

In 1843 Sarphati married Abigael Mendes de Leon, daughter of ex-parnas Jacob Mendes de Leon (1784-1842). Rabbi Ferrares consecrated the wedding. Sarphati's father-in-law, a freemason, had ideas, which at that time certainly were progressive. He was a member of the town council of Amsterdam, he established the school for the poor of the Portuguese-Jewish children in 1814 and in 1818 helped establish the settlement of the Society for Charity in Veenhuizen, a project trying to combat poverty and beggary by letting people earn their own living in agriculture. Jewish beggars and poor people could also be sent to Veenhuizen at the expense of sedaca, Hebrew for charity (tsedaka). Veenhuizen entailed a modern idea because poverty and hunger at that time were thought to be natural phenomena in a God given order. Wealthy people were expected to make life for the poor more bearable, by giving them alms, gifts and doing 'good deeds'. The idea of fighting inequality by providing work could at that time perhaps be called revolutionary. The colonies became famous and were visited by local as well as foreign guests. Although the intention was idealistic, the result was less than successful; the fate of the settlers was miserable and the isolated life led to quarrels and tension. They had almost no chance to return to society.

Sarphati shared the opinion of his father in law that beggars, vagabonds, paupers and 'ordinary' poor should not get alms but opportunities, education and work. However, he went a step further. He did not bring this into practice in the far away province of Drenthe, but in the town of Amsterdam itself.

The forties of the nineteenth century

Apart from his practice in medicine Sarphati was involved in 1842 in the establishment of the Netherlands Society for the Advancement of Pharmacy and in 1945 in the establishment of the Public School for Commerce and Industry. In 1847 he started the Society for the Advancement of Agriculture and Land Reclamation. In that year he obtained a permit to collect the ashes of fireplaces, refuse and human manure. The collection of excrements by such a service improved hygiene and public health. The dung could be used for agriculture. By reclaiming land it could be made fit for growing crops. Decent behavior, employment, and public health: with these plans all kinds of problems were tackled at once.

In his capacity of physician for the poor, Sarphati protested at the city council in 1844 on behalf of the parnassim against the growing objections, made by Christians in Amsterdam, against burials on Sundays. The protest by Sarphati was taken notice of and burials could henceforth also take place on Sundays. In the forties of the nineteenth century Christians were inspired by a religious fervor that was not present before. This resulted in proselytism and the institution of Sunday rest, also for non-Christians. Sarphati showed vigorous resistance against this Christian dominance. For example, he zealously worked for the establishment of Jewish kindergartens, where toddlers would not be put at the risk of being converted.

In 1846 an epidemic of 'red fevers' erupted, presumably scarlet fever, which attacked many more Jewish victims than the cholera outbreak before. Two new poor doctors were appointed: J. de la Mar and I. Teixeira de Mattos. Sarphati was supposed to accompany them, but that came to nothing: he was inundated by all his other activities. In 1846 the hospital management argued that Dr. Sarphati "doesn't apply himself diligently to the care of the needy". Sarphati could only agree with them and resigned. The six months salary, which they still owed him, he donated to the hospital.

The fifties

During the fifties of the nineteenth century the city got ready for the "Second Golden Age". Political, social and economic developments evolved very rapidly and the changes in everyday life were great. The Portuguese community was also positively affected during this period. The establishment of the Constitution in 1849 had managerial consequences for the structure of the community. Most of the officiating committee members made way for a new generation. One of the new members was Sarphati. He was a member of the council of the Portuguese community as from 1854. Consecutively he was gabay (treasurer) and chairman of the collegiate of parnassim (the daily management) and chairman of the church council (general management). As council chairman of the Portuguese-Israelite church council he put up a dazzling amount of subjects for discussion. He diligently worked for changes in the administrative regulations. Amongst others he stipulated that the presence of parnassim in the synagogue on holidays was compulsory. He had re-examined and reviewed all rules and regulations for persons working for the community.

Furthermore, Sarphati was a member of the committee of the Meat-Market, the brotherhood of the Santa Companhia de Dotar Orfas e Donzelas (monies disposed by lottery to orphans and young women) and of the Poor School, where he was against the proposed closing of the school. He was mohel (circumciser) and administrator of the society of circumcisers, Berit-Itshac. He also emphasized the responsibility for and maintenance of the church ornaments: on his initiative the first stock-taking of ceremonial objects took place. Sarphati granted each year either a carpet, an ornamental coat or some other precious object to the community.

Beth Haim in Ouderkerk

It is perhaps also thanks to Sarphati that the Beth Haim in Ouderkerk still is in a relatively good condition.

Around 1850 the water management of the cemetery was badly neglected and the graves were in danger of sinking into the peat because of superfluous and overflowing water from the ground, the rain and the rivers. The riverbank crumbled away. The problem of deciding who was responsible for the repair of the banks had kept the minds of many people busy for years. Did the Provincial government or the Portuguese community of Ouderkerk have to pay for this maintenance? Sarphati put an end to these discussions; he decided that the Portuguese community was responsible and that the repair should start as soon as possible. As from 1851 Sarphati , as a liberal, was a member of the Provincial government and thus had easy access to the jurisdiction of the water and the polder boards.

As one neither wanted to dig into the earth of the cemetery nor to vacate any graves, an expensive but efficient solution was proposed: widening of the bank by one yard and strengthening it by two to three decimeters (palms), in simple terms making it 20 to 30 cm higher and one meter wider. After further delay he asked the polder management to press the Provincial government for improvement of the banks; this request was then forwarded to the Portuguese community. It had the required effect: approval for the extension into the water was received. Together with Samuel Mendes da Costa, grandfather of the famous sculptor Joseph, and during this period contractor of the Portuguese community and member of the Society for Land reclamation for Agriculture, he prepared the project for the necessary permits and financing.

In 1856 the work was finished and a maintenance contract was concluded for the following period.

Beggars in Beth Haim

In 1849 Sarphati was co-founder of the Society for the Benefit of Israelites in the Netherlands, counterpart of the Society for Public Benefit, which did not admit Jews. The Society for the Benefit of Israelites did its utmost to improve education and schooling, an Association for the Procuring of Employment was established, a kindergarten (enabling also women to work) as well as a savings- and deposit bank. The Society also fought against beggary. The contention was that a prohibition would give the beggars an incentive to learn a trade or to report for employment.

It disturbed Sarphati deeply that Portuguese-Jewish beggars were at that time walking around in the cemetery and in the village of Ouderkerk. The poor begged at funerals, at the laying of tombstones and at the yearly memorial services.

In the year 1855 he/Sarphati issued an ordinance, in the name of the management of the cemetery, prohibiting begging on the grounds of the cemetery.

Those who contravened this prohibition and nevertheless arrived on the barge in order to beg, were noted down in a book of grievances and could thereby loose their allowance of sedaca. Big posters announcing the ordinance were hung near the Snoge and in Ouderkerk. These are now in the Amsterdam City Archives.

A dissecting hall

Opposite the Snoge an old building was demolished. On that spot (next to the Mozes and Aaron Church) a new police building was to be erected, with a physiological-anatomical lab. Sarphati heard of these plans and immediately went into action: "the allocation would be in conflict with the dignity of our church building". The parnassim were also dismayed: "in a neighborhood almost solely inhabited by Jews, there could be no place for such a building, which is in conflict with the dignity that Jews render to their deceased". Jewish law only exceptionally allowed dissection. They would be confronted almost daily with the arrival and removal of corpses. Despite the protests it was decided to establish the laboratory with dissection hall on that place, but the transportation of the bodies was adapted: the entrance was as far away possible from the Snoge, a side entrance. The complex, which was brought into use in 1868, was again demolished in 1968.

Palace, bread, banks and relief organizations

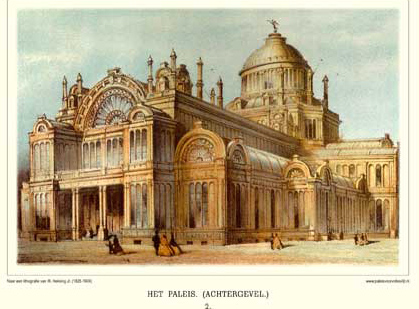

Meanwhile, Sarphati busied himself with a new idea: the establishment of the “Paleis voor Volksvlijt” : the Palace for Industry of the People. On one of his trips he had seen the Crystal Palace in London from which he got the inspiration: such a palace of glass and metal should also be built in Amsterdam. For this purpose he established a company in1852 and on September 7th, 1852 King William III laid the foundation stone. (During clearing work on the lot on Frederiksplein in 1961, a cylinder was found inside one of the foundation piles of the Palace. This cylinder contained a document mentioning the names of the king, of Sarphati and others who were present at the ceremony on that 7th September.)

In 1855, when discussions about the building of the Palace continued were going on (the city council of that period had already decided in 1853 that there was no plot available 'for the mentioned purpose'), he temporarily concentrated on a different problem: the bad quality of bread. The rumor went around that even water from the canals was being used for its preparation. Sarphati inaugurated in 1855 the Society for Flour and Bread Factories on the Vijzelgracht and for the first time the population of Amsterdam ate good and cheap bread.

After bread, Sarphati concentrated on banking: he established the Netherlands Credit and Deposit Bank, the National Mortgage Bank, the Netherlands Building Society and the Amstel Hotel Company which financed the building of the Amstel Hotel. He was also active in Jewish organizations such as Pekidim and Amarkalim and the Alliance Israelite Universelle. Pekidem and Amarkalim, established in 1809, occupied itself with the collection and distribution of monies for the Holy Land. The Alliance, established in 1860, supported victims of pogroms from all over the world. Sarphati was chairman of the Dutch division, which was established in 1864.

Opening of the Palace

The festive opening of the Palace of Industry took place on August 16th, 1864. Almost all of Amsterdam came out to admire the imposing palace with its grand glass dome and hundreds of arched windows. There were speeches and Prince Frederik Hendrik was present. He knighted Sarphati on that occasion, an orchestra played and in the evening there were fireworks above the Amstel. The fame of Sarphati had risen to great heights.

For Sarphati himself, a dark cloud hung over this day. A few months before, in May, he had lost his wife. He mourned over her and said that he missed her like a small fleck in a huge space and therefore he was 'dull and indifferent' to all expressions of praise. His wife had been part of a small group of family and friends who had supported him in all his plans and was also his sounding board.

His loss weighed heavily on him but he tried to make a new start

However a bowel illness undermined his health. He could not be present at the opening of the first exhibition of the Palace of Industry on June 21st, 1866, which again was a big feast. His father Emanuel, however, was present and thought that his son was getting better. The dismay was therefore so much greater when Sarphati died two days later. He was 53 years old.

Man of action

He was buried on June 25th. The evening newspapers reported in detail about the funeral, which was described as having been simple but impressive. Thousands of people stood in severe mood and sorrowful along the canals, the streets and bridges around the house of mourning on Herengracht 598, near the Amstel. In front of the house gathered relatives, friends and acquaintances. 'And Shmuel died and all of Israel mourned him' would later be engraved on his tombstone.

30 carriages followed the hearse. Also three steamboats sailed to Ouderkerk. There was not enough room in the Rodeamentos House for all the people who wanted to pay their last respects around the bier.

The tomb of Sarphati was simple. He lies next to his wife Abigael. Her stone has Portuguese inscriptions; the one of Sarphati has a Hebrew text. In a half circle at the top it says: And the Eternal called Shmuel and he said "I am ready" – here I am (1 Sam.3:4). Further he is described among others as religious, honest and a courageous man of many deeds, one of the prominent persons of the state, taken from proverbs of Genesis, Ecclesiastes, Kings, Chronicles and Job.

After his death it appeared that not much was left of Sarphati's financial means: he had invested all his money in his enterprises. There were big debts. His friend A.C. Wertheim took care of the settlement of the estate.

Much of what Sarphati has achieved meanwhile got lost. For example, Sarphati always resisted the closing of the Poor School, a form of special Jewish education. Four years after his death the school was closed. The Palace of Industry was a longtime frequently visited place of 'exaltation' and amusement, but on April 18th, 1929 it burned to the ground.

Nevertheless the city of Amsterdam still has much to show in remembrance of this great contributor to its development, as mentioned in the beginning of this article.

His name pops up over again. Also the Amstel Hotel, one of his endeavors, though not recalling his name, still the most eloquent hotel in the city, is part of his legacy.

Lydia Hagoort, with thanks to Ben Noach

This article is an adaptation of the chapters about Samuel Sarphati in her study 'The Beth Haim in Ouderkerk at the Amstel : the cemetery of the Portuguese Jews in Amsterdam 1614-1945' (Hilversum 2005)

ISBN90-6550-861-9

The part about the opening of the Palace of Industry has been taken from an article by M.G. de Boer in the Yearbook of the Dutch Society for Industry and Commerce 1778-1928. Jubilee edition (1928) 35-38.

The piece about the name Sarphati and several anecdotes have been taken from the chapter about Sarphati in the book of Jaap Meijer: 'They left their traces/mark : Jewish contribution to Dutch culture (Utrecht 1964).

The Hebrew text on the tombstone was translated by Hans Rodrigues Pereira.

Lydia Hagoort published in January 2013 an elaborate biography (416 pages) on Samuel Sarphati:

"van Portugese armenarts tot ondernemer"

ISBN10 - 9059373294, ISBN13 - 9789059373297.

Amstel Hotel - Amsterdam